There are 12 women in the room, myself included, all seated in a circle of plastic folding chairs. Some of us are holding foam cups full of the free instant coffee offered to us at the door. I am on my second cup already.

“Hi, my name is Angela and I’m a sex addict,” the woman sitting directly across from me says.

“Hi Angela,” the rest of the women respond in unison.

“This week, I … um … I’ve been struggling with watching porn again,” she continues.

Sweat drips down my forehead and rests on top of my eyebrows. I listen to each of the women, in a clockwise direction, take a turn speaking. Soon it will be my turn. I feel a knot forming in my stomach and I’m overcome with a wave of nausea. They all continue to confess their transgressions of lust, masturbation, and late night pornography-viewing escapades. The woman to my right, Rebecca, finishes speaking. It’s my turn.

Advertisement

“Hi, I’m Samantha …”

I pause for a second, wondering if I have to say the next line. The group leader is looking at me with her eyes wide. I think she’s staring into my soul.

“… And I’m a sex addict.”

I was 23 when I attended my first Sex Addicts Anonymous meeting and back then I believed with all of my heart that I had a sex addiction. For my entire life, my evangelical Christian community had told me that any sexual act, thought or desire outside of marriage between a man and a woman was a grave sin against God. The path to my salvation had hinged on my ability to remain sexually pure. When I confessed my “sexual sins” to my church mentor in 2014 after years of struggling to ignore my sexuality, she suggested I seek recovery for my addiction.

I was in SAA for just under a year but my time spent there and the events that led me to those meetings had a lasting impact. I now know that I was never a sex addict but instead was a product of a dangerously insidious purity culture that still thrives in many religious contexts today.

My parents weren’t raised religious, but when I was in the second grade my dad found Jesus in a hospital waiting room. My mom almost died of cancer that night, and when she survived, my parents vowed to follow God for the rest of their days. A week later, I was in a Sunday school class at the Methodist church down the road.

Advertisement

It was there that I learned about sin and salvation. I was told God created the world, was constantly angry at humans for messing up, and then sent his one and only son to die so that everyone else would be free. Our teachers warned us about sin every chance they got. I was riddled with guilt my whole childhood and prayed to God every night before bed for forgiveness.

In the sixth grade, I heard about “sexual sin” for the first time. Our youth group leader told us that God saved her from her lustful ways. She said she used to put her worth in men and in finding love. She explained she was empty, dirty and lost until God found her. “God saved me from my sexual sins,” she said. She cried as she told us her story.

I went home that night and prayed to God for hours. I was scared that something like that would happen to me, so I pleaded with God to save me from the same fate.

“In the sixth grade, I heard about ‘sexual sin’ for the first time. Our youth group leader told us that God saved her from her lustful ways. She said she used to put her worth in men and in finding love. She explained she was empty, dirty and lost until God found her.”

In high school, I dove even deeper into my Christian community and started attending a high school ministry group called Young Life. We talked a lot about sexual sin ― about things like sleeping with your boyfriend, masturbating or watching porn. I was curious about sex and about my body and was constantly thinking about what it would be like to make out with the guy who sat behind me in chemistry class. I was certain it would feel good but I was terrified of disappointing God. Sex was on my mind ― just like most other teens ― but underneath, my thoughts thrummed a steady hum of shame.

Advertisement

I started watching porn my sophomore year after someone in my algebra class told me about a new site called Pornhub. I was instantly hooked. Porn was a secret, always available outlet for all of the sexual desires I had to keep hidden. I could explore my body and my sexuality without anyone else finding out. I felt excitement every time I watched it, but that rush was immediately followed by the shame of knowing that I was committing sexual sin.

In college, I became a Young Life leader and continued investing time in my church community. I was still watching porn often, but I was trying to wean myself from it while simultaneously maintaining the appearance of purity that my community revered. After a while, though, the weight of knowing that God knew what I was doing felt too heavy to carry, so I decided to confess my sins to my friends and hopefully get help.

Everyone told me they were proud of me for being honest about such a dreadful sin. I was “brave” for my vulnerability. When I told my mentor, she congratulated me on taking such an enormous step of faith and recommended a few “sex/porn addict” support groups, one of which was SAA. I was hesitant at first, but I already had a friend who attended the group so I tagged along with her the following week.

Our women’s-only meeting was on Tuesday nights at a Baptist church down the road from my apartment, and sometimes I would see men walking into their meeting across the hall. I tried a co-ed meeting once but I felt so anxious and embarrassed that I threw up my Chick-fil-A sandwich the second I got home.

Everyone in my group was a devout Christian, all trying desperately to avoid our sins of lust. After the first few months, I was assigned a mentor. Her name was Ella and she had been a recovering sex addict for over five years. She was bright and bubbly but her shoulders hung low. She and I would meet 30 minutes before each weekly group meeting to go over what I had been working on.

Advertisement

There was one meeting with Ella where I was feeling particularly anxious. I had developed a crush on a co-worker and he had reciprocated my interest. I was nervous to tell Ella that we made out at a party the previous weekend. In SAA, we were encouraged to stay away from any sort of sexual activity, including kissing.

Just as I suspected, Ella was shocked at my confession. She didn’t think it was a good idea for me to be making out with random guys while I was dealing with my recovery. I stayed quiet and agreed with her but I felt uneasy on my drive home that night.

For the first time since I started attending SAA, I was angry. I was mad at Ella for telling me what to do with my situation ― and at all of the other people from my church who had done the same.

Tears poured down my face and anger welled up inside me as I drove home. But then, as quickly as I could, I attempted to quiet my mind and prayed to God for forgiveness.

In the following months, no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t shake what I felt after that meeting with Ella. I was now hyperaware of the shame in my life and all around me. It was palpable. I would sit in church services, Bible studies and SAA meetings, trying to drown out my anger with prayers to God. But it was too late. I had let the anger in and I could no longer ignore it.

Advertisement

“I finally realized that my whole life had been made up of other people’s decisions ― decisions based on fear, misinformation and attempts to control. I now saw the truth: My sexuality, my body, the things I felt, the questions I had, and my desires weren’t evil.”

By my 24th birthday, I had left Sex Addicts Anonymous. I wasn’t planning on it at the time, but I ended up leaving my church community, too. The anger I allowed myself to feel after that meeting with Ella was the first time I truly let myself push back against what my community believed. It was the first time I trusted myself and there was no turning back after that.

I finally realised that my whole life had been made up of other people’s decisions ― decisions based on fear, misinformation and attempts to control. I now saw the truth: My sexuality, my body, the things I felt, the questions I had, and my desires weren’t evil. None of it meant something was wrong with me. I wasn’t addicted to sex and I didn’t need the help I had been convinced I needed.

Walking away was terrifying because I spent my whole life believing what my community had told me and I was still worried I might be making the wrong choice. Maybe God would smite me and condemn me to hell. Maybe my life without the church would be miserable. But choosing to turn away from shame, being able to listen to the intuition that had been inside me all along, felt well worth the risk.

It’s been almost seven years since SAA, and thanks to therapy and people in my life who encourage me to be myself on a daily basis, I’ve found peace with my experience. I lost a handful of close friends after stepping away from my faith community, but my family was supportive of my decision, despite their religious beliefs. Now years later after walking away, I can say with confidence that I never had a sex addiction.

Advertisement

It’s difficult to find one universal definition for “sex addiction” because the term is highly debated by medical experts and isn’t recognised by a large part of the psychology community as a diagnosable addiction.

The DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) no longer recognises sexual addiction as a mental health disorder, one of the reasons being because people don’t experience withdrawal symptoms or the physical need for sex like they would with drugs or alcohol.

It also has to do with the fact that oftentimes the person diagnosing a sex addiction carries their own moral judgments or biases related to sex. Instead of sex addiction, people now often use compulsive sexual disorder to describe a “persistent pattern of failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges resulting in repetitive sexual behaviour.” The use of both terms is still controversial, especially as more research is being done around these topics.

What many medical experts do agree on is that a lot of people who claim to be “sex addicts” are not actually engaging in more sexual behaviour than normal, but instead come from highly religious backgrounds and feel more levels of moral guilt associated with their sexuality. New research from the Journal of Abnormal Psychology found that most of a study’s 3,500 participants weren’t taking part in higher amounts of sexual activity, but instead carried more religious guilt about their sexual actions. These feelings of guilt often lead to a greater struggle to stop unwanted behaviour.

For most of my life, I was told my sexual desires were a sin against God. I believe this led to personal shame and the belief that I couldn’t control my own natural sexual urges. But I now know my curiosity about my sexuality and my body was healthy. When I removed the strict moral lens of religious purity culture, everything became crystal clear.

Advertisement

The evangelical church’s view on sexual purity and sex addiction is harmful. For individuals like me who grew up in these environments, the concept of purity can foster shame, isolation, and compulsive thoughts and behaviours. That compulsiveness and the cycles of shame we can experience are then often wrongly mislabeled as sex addictions.

For our society as a whole, it’s obvious how these teachings have a far wider impact and can lead to a lack of comprehensive sex education, a lack of accountability, misogyny, homophobia, and sometimes even the sexual violence that we see in our culture on a daily basis.

I’m not sure that stories like mine will ever change the evangelical church. Though I hope its leaders might realise how harmful their teachings are and take action to do better, I know that these beliefs are the foundation of the church and, therefore, unlikely to change. However, I am hopeful that by speaking out, I might help others who are going through what I went through. We rarely talk about experiences like mine, especially publicly, but it’s much more common than you might think, and I want others to know you can live your life happily, confidently and without shame.

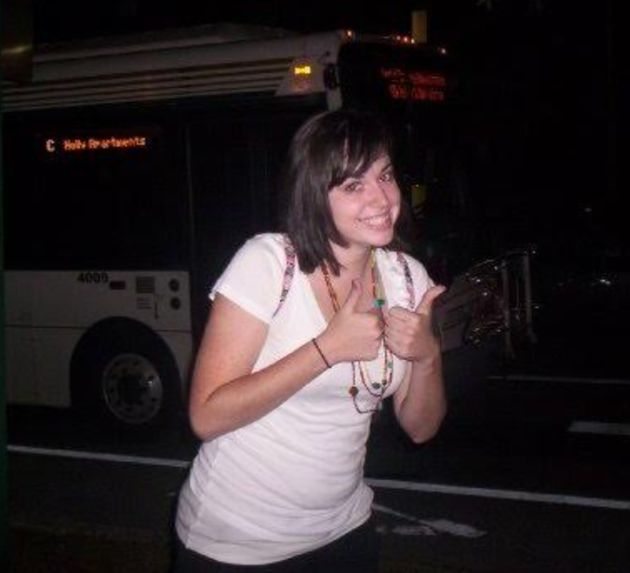

Samantha Boesch works as a writer and editor in Brooklyn, New York. She writes about health, wellness, and sexuality, and is studying to become a sex educator. You can connect with her on Instagram at @SamanthaBoesch or on Twitter at @SamanthaBoesch.