“I can’t stop thinking about him,” my client said. “I even daydream about our wedding.”

She stared at me intently from across the coffee table where our two cups of peppermint tea sat untouched. When I didn’t respond, she lowered her voice and said, “I just feel like we’re meant to be together.”

I’d been counselling this client long enough to know the “him” to whom she was referring was not her husband of 15 years. Instead, it was the much younger man she’d met two months prior at a yoga retreat.

Advertisement

“OK,” I said, reaching for my mug. “Let’s try to figure out why this person has such a hold on you.”

My client could have easily spent another hourlong session obsessing over “hot yoga guy” — which she’d done many times before — but I wasn’t going to let her. My job as a therapist was to help bring deeper awareness to her emotional experience and to identify what was simmering just beneath the surface, driving compulsive thoughts and behaviours. In this case — limerence.

Almost everyone, at some point, has experienced a romantic crush. However, unlike a typical crush, limerence is defined by obsessive ruminations, deep infatuation and a strong desire for emotional reciprocation — an unfulfilled longing for a person.

According to Dorothy Tennov, American psychologist and author of “Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love,” limerence “may feel like a very intense form of being in love that may also feel irrational and involuntary.”

Advertisement

Tennov identified the most crucial feature of limerence as “its intrusiveness, its invasion of consciousness against our will.”

Limerence differs from the liminal dating phenomenon known as “situationships,”or “we’re dating but we’re also not quite dating.” While both feed off uncertainty, when someone is experiencing limerence, they often prefer the idea of their limerent object (LO) over being with that person in real life. In fact, they might actually feel something akin to disgust when in the physical presence of their LO. I understand this feeling all too well — my own limerent object held my heart and mind hostage for years.

Levi and I met on the first day of my sophomore year of high school in the mid-’90s. I was wearing baggy denim overalls and combat boots, and my blond hair was long and parted down the middle. I’d just gotten my braces off and my teeth were the straightest they’d ever be. Our relationship unfolded to the soundtrack of Baz Luhrmann’s “Romeo + Juliet” and “August and Everything After” by The Counting Crows. There were knowing looks and homemade mixtapes — filled with Dire Straits, Jewel and Better Than Ezra — passed discreetly in the hallway between classes. We were running through the wet grass, desperately wanting, but never quite having. We never actually dated.

Advertisement

Earlier that summer, my family — minus my father — had moved to Woodstock, Vermont, from Boston. My parents were unhappily married, but instead of divorcing, they decided to lead two separate lives. My mother, a retired school administrator and former nun, moved to rural Vermont, and my dad stayed behind to work at his law firm.

Levi wanted to be my boyfriend. He was unwavering and absolute with his feelings as only a love-struck teenager could be. In response, I held him at arm’s length while dating other people. But late at night, I’d let him sneak into my bedroom on the top floor of my family’s rambling farmhouse and we’d lie tangled up together underneath the shiny soccer medals and enormous round window that hung above my bed. By homeroom the next morning, it was like it never happened.

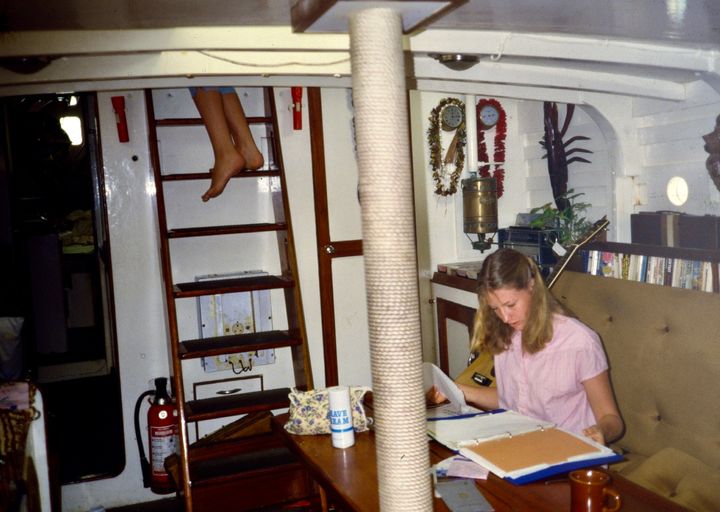

Courtesy of Anna Sullivan

Advertisement

Nobody needed to tip-toe around my house. After the move, my mother’s drinking escalated to the point where she often passed out in her bedroom before dinner. My father visited us once or twice a month. He spent the weekend arguing with Mom and left without saying goodbye. On Monday morning, I’d wake to find him gone and a pile of cash on the kitchen counter. By the time I left for college, my sister and I were basically parenting ourselves.

After college I moved to Manhattan. I casually dated — and even had a few serious relationships — but I’d be lying if I said I didn’t think about Levi. I thought about him a lot. Out of nowhere, his image would pop up, haunting my consciousness like a ghost. Memories of us lying in my twin-size bed, bathed in moonlight, played on a loop with Jewel crooning in the background, “dreams last for so long / even after you’re gone.” Eventually, I began to question whether I still had feelings for this person. Was he the one who got away?

The strange thing was every time Levi and I happened to be in the same city at the same time, I avoided seeing him. Something prevented me from exploring an actual relationship with him in real time. A therapist reasoned it was hard for me to let go of his memory because we never had closure, but her take always felt slightly off. My feelings for Levi felt primal — instinctual. Bone deep. Something I couldn’t shake.

Advertisement

In my late 20s — practically estranged from my father by this point — Levi reached out to me. It was a basic missive, but still, reading his name in my inbox sent an electric current up my spine. I felt like I’d been plugged into a wall. I replied and said I was good, even though I wasn’t. I’d just ended a long relationship that I thought was going to end in marriage. I was fleeing to New Mexico to pursue a graduate degree in counselling. My life was poorly packed in 20 boxes, stacked haphazardly in my parents’ garage. “How are you?” I redirected.

Levi invited me to coffee. I lost five pounds before we met at a familiar spot in our hometown the following week. I arrived wheeling a suitcase because I was hopping a flight to Santa Fe later that afternoon. He looked a lot different in person than he did in my imagination — older, his hair thinning.

Seeing him was like a controlled science experiment. He mostly talked about himself, and I felt relieved when it was time to go. Later that afternoon, as I boarded my flight, he emailed me: “If you’re still in town let’s meet for a drink….” His invite gave me goosebumps. I never responded.

Advertisement

Eventually, I finished graduate school and began my career as a counsellor. I met my husband, Alex, in Santa Fe, and we later got married and had two children. The years passed and we built a beautiful life together, though it hasn’t always been easy. Our older son was born with many challenging issues. Shortly after his first birthday, I lost my mother to fast-moving bone cancer. Less than two years later, I was diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent a unilateral mastectomy and adjuvant hormone treatments that pushed me into premature menopause.

Through it all, Alex stuck by me. He held my hand at my oncology appointments. He did the lion’s share of parenting our two toddlers while I recovered from surgery. He rocked me back to sleep when I woke in the night riddled with anxiety about mortality and motherhood, and he made me laugh when all I wanted to do was cry. Sometimes, I look back on those first years of married life and wonder how we ever made it through. But somehow, we did — together.

And yet, every now and then, I thought about Levi. He’d enter my consciousness without warning like a spectral whack-a-mole or a goblin. And then, just as quickly, his image would disappear, leaving me feeling guilty and ashamed. Even though I didn’t feel physically attracted to this person, the thoughts felt like a betrayal to my husband, who I loved. My sweet husband, who nursed me back to health after cancer and snaked the shower drain whenever my hair clogged it. How could I still be thinking of some random person from my past? I was starting to think I needed a seance for my psyche. Instead, I decided to utilise my professional training as a therapist to identify — once and for all — the origin of these adolescent ruminations.

Advertisement

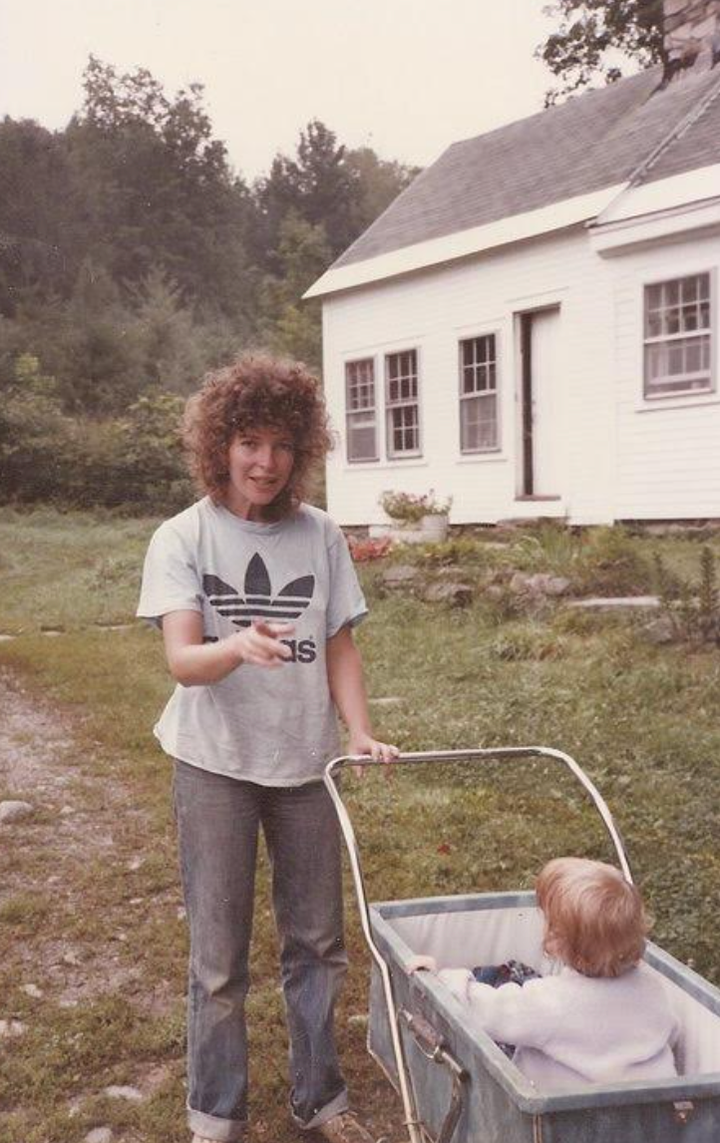

Courtesy of Anna Sullivan

I first learned about attachment theory in graduate school. The theory, originated by British psychiatrist John Bowlby in the 1960s, posits that attachment is formed during the first few years of life and determined by the quality of relationships between children and their primary caregivers. It offers a psychological framework for understanding how early relationships with caregivers impact interpersonal relationships, behaviours and emotional regulation throughout life.

Psychologist Mary Ainsworth later expanded on Bowlby’s work by conducting the “Strange Situation” experiment where babies were left alone for a period of time before being reunited with their mothers. Based on her observations, Ainsworth concluded that there were different types of attachment, including secure, ambivalent-insecure and avoidant-insecure. Later, a fourth type of attachment was added, disorganised attachment, based on research performed by Mary Main and Judith Solomon, two psychologists from the University of California, Berkeley.

Advertisement

During my practicum, I took a quick online assessment and wasn’t at all surprised to learn that I have anxious/insecure attachment — the unfortunate combo of disorganised and fearful-avoidant. Learning about my attachment style was a critical first step toward gaining a deeper understanding of how I operate in relationships. For instance, it made me recognise my tendency to disconnect during difficult emotional experiences. My college boyfriend referred to this behaviour as “going into Anna land,” which looked like avoiding emotionally charged conversations, daydreaming and pulling away.

Over the years, the more I learned about attachment theory, the more I wondered if my anxious attachment and age-old coping mechanisms had something to do with Levi? They both seemed to share deeply entrenched and unconscious patterns of behaviour, and there seemed to be an obvious commonality between the two — fantasy.

When I was young, I adopted various mental and emotional coping mechanisms to help me feel safe. I carried these limerent strategies — detachment, avoidance and fantasy — into adolescence. Back then, I needed to escape the reality of my childhood home — my sad, lonely mother and my emotionally unavailable father. My limerent object became the lightning rod for all my emotions, both good and bad. My relationship with Levi helped to ease my insecurities and fear of abandonment, but limerence becomes pathological when a person prioritises the fantasy version of someone over the real, live version of them — especially because those two versions don’t often add up.

Advertisement

It took me a long time to distill the idea of my LO from the reality of my experience. Love demands a willingness to meet the other person in the moment, and the truth is, some nights I’d hide from Levi — in a closet or my sister’s room — as he wandered around my dark, empty house looking for me.

Coming to terms with how — and why — I created these maladaptive coping strategies was a pivotal turning point in my emotional development. As a child, I longed to grow up with answers and a sense of certainty — to be taught to believe in things like God and the Red Sox. During adolescence, my limerent object became my mental, emotional and spiritual bypass to get me through. As an adult, I was still using archaic coping mechanisms as a means to self-regulate. I knew that if I wanted to be fully autonomous and present in my life, I needed to let them go.

These days, as a mother and wife, I understand that love is an action, not just a feeling. I am responsible for creating my own happily-ever-after. While it’s impossible to have all the answers, I try to be honest with myself and others about the things I don’t understand. I believe that showing up and being present with the people I love, even when it’s difficult, is the best thing I can do — like when my son has a sensory meltdown and I sit with him until he stops screaming, or when my husband and I have a disagreement, I stay in the room and work it out.

Advertisement

Equally difficult, I allow — often force — myself to witness moments of beauty — like how my younger son still loves to climb into my bed each morning and press himself into the folds of my body. I know these moments are fleeting.

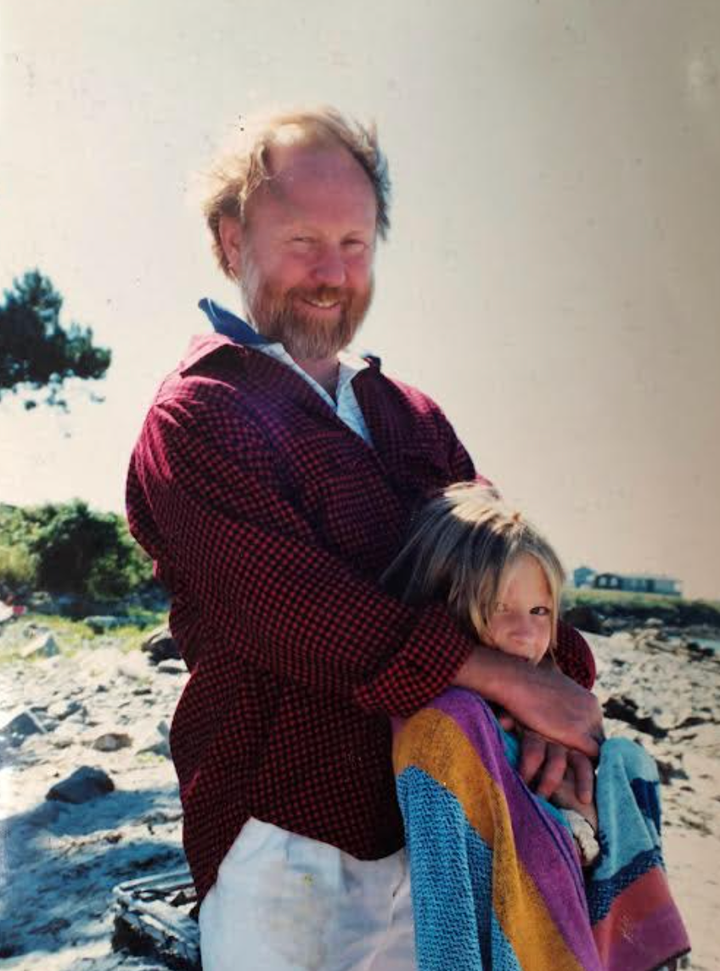

Courtesy of Anna Sullivan

Limerence is not love. It’s born from an unmet psychological need, and I believe that it can only be extinguished through the act of self-compassion. This involves the ongoing practice of forgiving myself for the mistakes I made when I was young, and forgiving my parents for their limitations, too. The truth is, my parents often failed me, but that doesn’t mean that they were failures. I know they loved me and did the best they could.

Advertisement

Over time, I’ve gotten better at sitting with uncomfortable feelings like grief, shame, anxiety and sadness. Therapy has helped a lot. And Al-Anon, which taught me how to practice discernment, or “the wisdom to know the difference.” At the end of the day, I know that I’ve developed the skills and self-assurance to move through life’s challenges without needing to check out. I’m working to rebuild my self-esteem from within instead of seeking validation from others, and I’m much more aware when I turn to fantasy as a means of self-regulation (like binging a show on Netflix). Most importantly, I’ve come to accept that my deepest longings belong to me — these primeval yearnings cannot be filled by another person.

Occasionally, I still think of my limerent object. Levi will appear in my dreams or pop into my head at random times during the day, and he’s always a much younger version of himself. However, the memories now feel less charged, and slightly melancholic. I understand the longing for a person who was always there and never there. Like a ghost, he’ll forever roam the halls of my childhood home — lit up with moonlight — searching for someone to hold in the night.

Note: Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals mentioned in this essay.

Advertisement

Anna Sullivan is a mental health therapist, author and co-host of “Healing + Dealing.” She has written for The New York Times, Vogue, Cosmopolitan, HuffPost, Today, Newsweek, Salon and more. She is currently writing a book, “Truth Or Consequences,” about going through early induced menopause due to cancer treatment. Find more from her at annasullivan.net.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch at pitch@huffpost.com.