Sitting in my Brooklyn apartment early one Friday morning, sipping on a mug of strong coffee, my cell phone pinged. “The eagle has landed,” the text message read, and I quickly threw on a jacket, ran downstairs, and hopped on my bike to pedal about three miles south, to the historic neighbourhood known as Ditmas Park. Pulling up to the street I was looking for, I pumped the brakes to cruise into my friend Adam’s driveway, where an insulated lunch box was waiting for me on his doorstep. I carefully placed the precious cargo into my bike’s rear basket, and set off straight for home: Time was of the essence.

Back in my apartment, I breathed a sigh of relief that my roommates had already left for work, as I was about to attend to a task so embarrassing and so frankly disgusting that I would not want another soul to bear witness to it. Setting myself up in my bathroom, I unzipped the lunch box to reveal its contents: A zip-top plastic bag containing one perfectly formed human turd – yes, I’m talking about poop – still warm, naturally, from its brief stint inside the padded box.

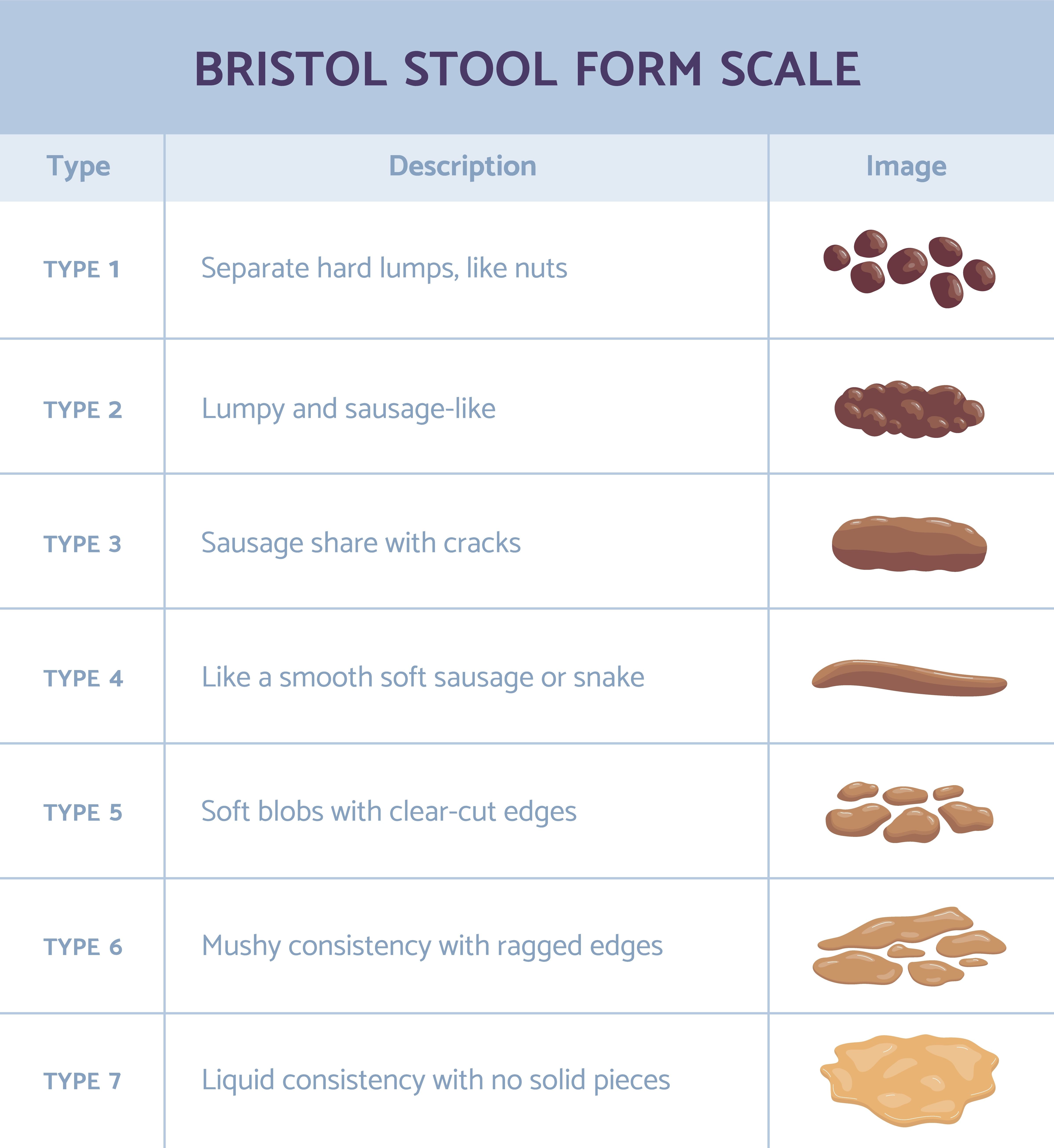

Working quickly in order to avoid introducing air into the bag – and also, let’s be honest, because the task was gross – I tipped a small quantity of saline solution into the bag, zipping it back up and using my hands (from the outside of the bag, of course) to mash the saline into the poop to approximate the thickness of a chocolate milkshake (my apologies for ruining that craving for you).

Once achieving that texture, I snipped a corner off the plastic bag, squeezed the brown mixture into a disposable plastic enema bulb, and lay down on my side atop a clean towel I had placed on the bathroom floor. Pulling my knees up to my chest, I reached behind me, squeezed the bulb’s contents into my rear, and browsed social media on my phone for about 15 minutes, at which point I placed my legs up the wall and waited for another 15 before going about my day.

What kind of a person would do something so astonishingly nasty and incredibly taboo? A perfectly normal one, I assure you – but also a very sick and desperate one. The process I describe above is known as a DIY or at-home faecal transplant, and I performed my first such treatment back in the fall of 2018. A

bout a year prior, I – a formerly very active, healthy, and vibrant 31-year-old – had become very, very sick, more or less overnight. Whereas my days used to be packed with such varied activities as researching and writing freelance journalism articles, biking all over my borough, cooking elaborate meals to enjoy with friends, and attending yoga classes, in that time I had gradually become housebound with symptoms such as joint pain, digestive issues, the confused thinking known as “brain fog,” and chronic fatigue that had me sleeping up to 18 hours a day.

By this point, I was no longer living, but just surviving, day in and day out, as I attempted to piece together what, exactly, had gone wrong.

Prior to my descent into chronic illness, the only sickness I had ever known was a short-lived cold or headache. Therefore, I was truly out of my depths when it came to sleuthing out the cause of my symptoms, which had been kicked off by a course of common antibiotics I took for a urinary tract infection in 2017.

Shortly after finishing the meds, I started to experience all sorts of bizarre things: My scalp itched incessantly as if I had lice, my extremities were hot to the touch and visibly inflamed, and my former stomach of steel suddenly had trouble digesting foods I’d eaten my whole life. At the time, I was living abroad in Mexico, and was forced to travel back to New York to seek medical attention.

At my first appointment with a naturopath recommended by a friend, the doctor looked up from the notes she was scribbling furiously when I mentioned the recent course of antibiotics. “Are antibiotics something you take frequently?” she asked. “Actually, yes,” I replied. I explained that throughout my 20s, I had been plagued by frequent and painful UTIs, and that doctors always prescribed antibiotics for them. Together, the naturopath and I figured out that I had ingested about 15 rounds of antibiotics in adulthood alone, and who knows how many as a child.

Today, it’s fairly well known that this class of drugs, while lifesaving in certain cases, is vastly over-prescribed and can negatively affect the health of the complex ecosystem that resides in our guts, known as the microbiome or microbiota.

There, up to 1,000 species of bacteria (ideally) live in harmony, forming the basis of our immune system and helping the body not only to digest food, but also to stave off invaders such as harmful bacteria and viruses.

But at the time, I didn’t know that antibiotics kill off both beneficial and pathogenic bacteria indiscriminately, a mechanism the new naturopath explained to me. Especially when overused, the drugs can permanently eradicate species of good bacteria in the gut, she told me, leading to system-wide malfunction in the body, and, potentially, symptoms such as irritable bowel syndrome, chronic sinus infections, and chronic skin infections.

The naturopath suspected that my myriad of symptoms stemmed from a gut depleted of various species of beneficial bacteria, and she suggested a course of treatment that included absolute avoidance of antibiotics and a diet rich in fermented, probiotic foods such as sauerkraut. But back at home, where I continued to research the issue online, I learned that the healthy bacteria in fermented foods don’t readily survive in the gut, which is, after all, a completely different environment than a strand of cabbage. The only known way to repopulate the gut with native strains of bacteria is through the infusion, to put it nicely, of faeces from a healthy “donor”: aka, a faecal transplant.

Known to livestock farmers – who observed that giving an enema made of poop from a healthy animal to a sick one could, in many cases, save the latter animal’s life – for at least a century, a faecal transplant consists of administering from a healthy subject to to the rectum of one that is sick, typically with the type of chronic diarrhoea that often leads to death due to extreme dehydration.

There, the beneficial bacteria from the healthy subject immediately start to colonise, restoring the immune system and helping the sick animal recover.

Eventually, the medical world caught on to what farmers had been doing for ages, and in 1958, the first faecal transplant in humans was used to treat the often-mortal gut infection known as Clostridioides difficile. Since then, FMT, as the process is known (short for faecal microbiota transplant) has been used regularly – with great success – to save the lives of patients struggling with this dangerous infection.

Unfortunately for patients facing the repercussions of antibiotics overuse, C. diff is the only approved hospital use for faecal transplants. For those who hope to treat chronic conditions such as IBS, liver disease, and neurocognitive disorders, the only settings that provide the treatment are private centres such as England’s Taymount Clinic and Australia’s Centre for Digestive Diseases, where in-patient courses of several FMT procedures can run up to $6,000 out of pocket.

In my case, as in the case of many others suffering from chronic illness, the only affordable option is a DIY one. Known as DIY or at-home FMTs, rogue faecal transplants have been something of a trend over the past decade.

Many websites, such as The Power of Poo, as well as tons of firsthand YouTube accounts exist to walk brave at-home FMTers through the process. Those suffering from sickness are advised to locate a “donor” who has a spartan history of antibiotic use, a balanced organic diet, and, of course, excellent digestive health. Many desperate people will go ahead with FMT based on those criteria alone, but others – like myself – will collect a potential donor’s “specimen” and have it laboratory-screened for common pathogens such as E. coli bacteria and Epstein Barr virus.

I identified three possible donors – among my closest circle of friends, who I knew wouldn’t judge me for my interesting choice of treatment – and tested their poo. Sadly, the results were mixed –clear evidence of our modern, toxic way of living – but Adam’s results were the best by far. After ironing out the unsavoury details with him, we entered into the rather unusual agreement.

All in all, I completed about 12 at-home FMTs, the process becoming decidedly less unsavoury as I noticed some positive changes such as an easing of my extreme chronic fatigue and fewer allergic reactions to foods.

Unfortunately, however, I didn’t experience the dramatic healing reported by many of the online accounts I had found, and I continued to dig into other possible causes of my symptoms. Eventually, towards the tail end of my treatments, I received a positive diagnosis for Lyme disease – which made sense considering that my symptoms started around the time that I had not only taken that course of antibiotics, but also immediately after a hiking trip to the Catskill Mountains in New York State, an area infamous for its high incidence of tickborne illness.

Using a just as off-the-beaten-path – but far less gross – treatment known as bee venom therapy, which harnesses the antibiotic and anti-inflammatory effect of live bee stings, I was able to fully recover my health, and have been well for more than a year. But I’ll always maintain – from a distance, of course – a certain level of respect for the healing power of poop.