You’re reading The Waugh Zone, our daily politics briefing. Sign up now to get it by email in the evening.

1 No.10 was a Covid chaos zone

The whole point of Dominic Cummings’ evidence was to provide the first draft of the history of the government’s handling of the pandemic. While his personal opinions on what went wrong can be dismissed, his eye-witness testimony cannot be easily shrugged off. And on that score, he didn’t disappoint, giving vivid accounts of the chaos in Downing Street as Covid hit landfall in March 2020.

His description of the events of over two key days allowed the public a glimpse of just how Boris Johnson runs, or doesn’t run, his government. On the “insane day” of March 12, while the PM clearly had no choice but to deal with Trump’s plea to join a bombing raid on Iraq, Cummings implied that his boss allowed partner Carrie Symonds’ to waste valuable press office time with complaints about a story about their dog Dilyn.

But it was the following day that was more telling and more worrying. First, a senior department of health official confided there was no plan for a pandemic. Then deputy cabinet secretary Helen McNamara allegedly said “I think we are absolutely fucked, I think this country is heading for a disaster. I think we are going to kill thousands of people.” Those words are sure to be pored over in any public inquiry.

Just as concerning was the picture painted by Cummings of the lack of data available, with him having to scribble on a whiteboard and an iPad a rough model of how many hospitalisations were happening, based on snippets of early info from NHS chief Simon Stevens. So too was the revelation that the Cabinet secretary Mark Sedwill so misunderstood Covid that he suggested the PM go on TV to tell people to have ‘chickenpox parties’.

2 Hancock was to blame for virtually everything

In what felt like a Whitehall version of the Assassin’s Creed video game, Cummings spent a lot of his time trying to eviscerate Matt Hancock’s reputation. The allegations were hugely serious, from lying about PPE stocks and testing in care homes to his decision to announce a 100,000 daily test target while the PM was “on his deathbed”. Yet the relentless nature of the onslaught (who cares how many times Cummings called for him to be sacked?) tipped from public interest to private vendetta.

What also furthered the impression that this was about personalities was his huge praise for Rishi Sunak and Dominic Raab (who both happened to be Brexiteers, while Hancock was a Remainer). Cummings’ curious memory loss about discussions of the EatOutToHelpOut scheme, plus his failure to criticise any decisions by old boss Michael Gove, suggested chairman Greg Clark was right when he asked if this was about ‘settling scores’.

Cummings also failed to fully credit Hancock for his strong push for a second lockdown in the autumn, while at the same time playing down the chancellor’s concerns about the idea. The lens was so skewed that he even said Sunak’s real worry was that the department of health could impose a circuit breaker but had no plan for what happened next. Most curiously, for a man who blogged at length about systems and processes, his real focus was on the central role of “brilliant” individuals, be they officials or ministers.

3 Boris Johnson was off his trolley

The vituperative attacks on Hancock felt like a sideshow compared to Cummings’ cold, matter of fact descriptions of Boris Johnson as being “unfit” to be prime minister. This was the PM’s former chief adviser saying he was never really upto the job, but he was at least better than Jeremy Corbyn. Johnson changed his mind so much, on everything from Covid to free school meals, that he looked “just like a shopping trolley smashing from one side of the aisle to the other.” Sunak was at his wits end about the trolley too, we learned.

Funnily enough the trolley analogy was first used by former Cameron spinner Craig Oliver to describe how Johnson wrote two different Telegraph columns for and against Brexit. But Cummings’s more damning charge was that the PM was fundamentally unserious about Covid policy. Perhaps his most telling line was this: “There is a great misunderstanding people have, that because it [Covid] nearly killed him, therefore he must have taken it seriously.” Narrator: he didn’t.

We heard of Johnson’s talk of injecting himself with Covid on live TV, his regret that he didn’t behave like the Mayor in Jaws and keep the beaches/shops/pubs open, his glib lines about letting ‘the bodies pile high’ and that the virus was “only killing 80-year-olds” (a charge pointedly not denied in PMQs). All felt like jokes that curdled quickly into a cold contempt for the very public he was meant to serve.

Add the claim Johnson “changes his mind 10 times a day” and disappears on holiday at key moments, and that’s a withering verdict on any politician, let alone a PM in a pandemic. No Wonder Johnson looked distinctly rattled when Keir Starmer quoted Cummings central admission: “When the public needed us most, the government failed”.

4 Cummings sounded as unserious as Johnson

Having learned from his Rose Garden press conference disaster, Cummings at least tried to open with an apology for his failures, including not hitting the “panic button” for lockdown earlier. Yet it felt like a strange humblebrag, that somehow he was a genius who spotted the problem but failed to convey that genius. It reminded me of the job interviewees who say their only flaw is that they are a perfectionist.

In a similar vein, his line that it was ”completely crazy that I should have been in such a senior position…I’m not smart” was a laughable attempt at self-effacement. In the next breath he expressed frustration that he wasn’t running the country instead of the elected PM, saying he tried to “create a structure around him..to push things through against his wishes”. Yet this was a man who stuck to his ludicrous specsavers defence for his trip to Barnard Castle.

Cummings’ line that Covid needed a “kind of dictator”, a scientist with “kingly authority”, just also proved how unserious he really is. So too were his references to Spider-Man memes and the film Independence Day (which the bereaved families group felt belittled the gravity of their loss). When he kept saying he felt like he was in a movie, he came across someone as woefully out of his depth as the boss he ridiculed. Asked if he too was unfit for No.10, he just sidestepped the question like a politician. And his charge that it was “crackers” that Johnson was in power suffered from the slight problem of his enthusiastic work to keep him there.

5 Governing properly is really hard, isn’t it?

The lessons learned about Cummings’ own character were possibly just as telling as lessons learned about the pandemic. His own credibility as a witness may already be fatally undermined by his Durham drive. But his testimony had some clear contradictions too. Criticising Carrie Symonds’ “unethical” interference in No.10 appointments may have provoked a hollow laugh from Sonia Khan, whom he had frogmarched by a policeman out of Downing Street without due process.

Most of all, when the crunch came, this would-be iconoclast, the arch-disrupter also revealed a telling lack of nerve in the real world: he revealed he didn’t push for lockdown earlier because he was “frightened” he would get it wrong. That in itself was a rare admission that running a government really is very different from running a referendum campaign. The stakes are all too real.

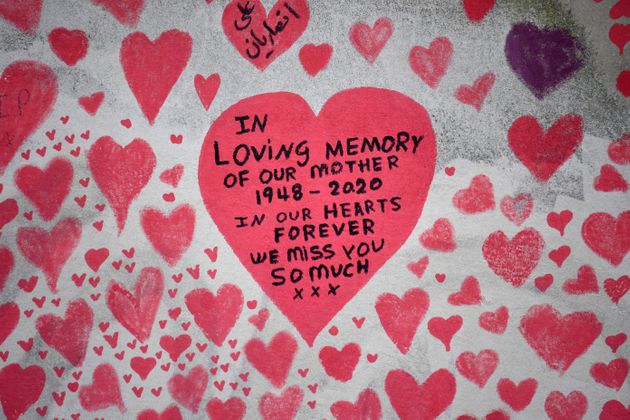

Cummings’ most serious charge was left for the latter part of his nearly seven hours testimony: “Tens of thousands of people died, who didn’t need to die.” The irony is that Johnson seems to have finally learned the lesson of hard lockdowns and slow releases only since January – after his chief adviser left office. Cummings today got his blame game retaliation in first ahead of the public inquiry. As the PM copes with the new Indian variant, his best answer to the criticism would be to get the current unlockdown right.